Priest Kirill Zholtkevich was born in Caracas in 1952. He began serving with his grandfather who had once been a priest and a missionary in Shanghai under the Tsar. From that time on, the boy was always in church. He graduated from high school in Humboldt and later studied at university, receiving a degree in dentistry. He studied at seminary and graduated from the Department of Architecture of Simon Bolivar Institute. Ordained by Bishop Alexander (Mileant), today Fr. Kirill is a cleric of the Diocese of Caracas of ROCOR. He started as a priest pastoring the “provincial” part of Venezuela: Valencia, Maracaibo and Puerto la Cruz, while also working as a dentist for thirty years. Today he is the rector of the Dormition Church of Caracas.

Priest Kirill Zholtkevich—Fr. Kirill, tell us about your spiritual journey. You literally grew up in church; your grandfather was a priest, and it predetermined your future.

Priest Kirill Zholtkevich—Fr. Kirill, tell us about your spiritual journey. You literally grew up in church; your grandfather was a priest, and it predetermined your future.

—My spiritual training began with my grandfather, a priest. He took me into the altar when I was four. Since then I have been in church and have always been surrounded by clergy. One day Vladyka Alexander (Mileant) came to us. He served in Los Angeles and then came to us in Latin America. I helped him. Once he called me and asked, “Kirill, what is your opinion about ordaining Prince Alexander Amilakhvari priest?” I replied: “Vladyka, that is your decision, not mine. He has always wanted, tried, studied, prepared... If a person is drawn to God, we should help and attract him, not reject him.” Vladyka suddenly said: “Well, I’ll tell you when to come to Los Angeles; I’ll ordain Amilakhvari priest and you deacon—you will help him.” It shook me up a bit. I was used to obedience, so I went. We served together, and I helped him as much as I could. But I also had to work in a secular job. Fr. Alexander and I only received money from services of need (treby), but mostly made our livelihoods from our “secular” life. Fr. Alexander was a civil engineer for an oil company. I was a dentist and worked at a public clinic for about thirty years. When a new Government came to power, I was discharged at some point, but it became easier for me because I was able to devote more time to God; besides, I was able to earn extra money in private practice.

Then Fr. Alexander died. Vladyka Laurus invited me, ordained me priest and sent me to the St. Nicholas Church. But after some changes there I was sent to pastor the whole of Venezuela. Later the parish in which Fr. Alexander Amilakhvari had served, taken over by a priest’s son, separated from ROCOR. From that time on I always traveled to the provinces regularly, as often as possible. When the pandemic broke out, public transportation stopped working. But I had to travel around the country to serve. I have an antimension from Metropolitan Laurus, which does not mention a specific church, so I can serve wherever I see fit. Since then I have been using part of my house for prayer and serving here regularly, including on the feasts. We currently have a problem with gasoline in Venezuela. If it’s not one thing, it’s another! And I am not able to travel to the provinces—there is shortage of gasoline, and it is quite hard to fit my schedule in with bus times. The old ladies who once received me are now dead. And there are no young people…

Bishop Alexander (Mileant). Photo: Iglesiarusa.info

Bishop Alexander (Mileant). Photo: Iglesiarusa.info

—Tell us about the history of the foundation of the parish.

—We had many parishioners from among Russian emigres, and many came after World War II. There were three churches in Caracas, plus a so-called “Ukrainian” church, whose parishioners were Ukrainian-speaking emigrants. They tried to separate from us, Russians.

The churches were packed with people on the great feasts, and some stood and prayed outside. Russians settled right where Russian churches were built. In the evening only Russian speech, not Spanish, could be heard in the vicinity. And now only three or four families are left; the others have either died out or moved elsewhere.

And now we have the following situation: There are few parishioners in all the parishes. The Catholics took the “Ukrainian” church because no one went there. The church in Maracay was taken over. And the Serbs asked me to pastor them, because they had no priest. Unfortunately, every year old parishioners go, and young ones are very indifferent to church life. Meanwhile, there are economic problems in the country. Most young people are well educated, so they look for well-paid jobs or move away altogether. In my memory, for example, the son and daughter of a parishioner went to Bogota. I cannot judge them—people are looking for a better life. As for new emigrants, they are totally different from those of the 1940s and the 1950s.

Our first church was built in 1947. There was a certain boom until the 1960s, but after the change of Government some emigrants got scared and started leaving. Most of them were professionals, talented in their trades, and strong believers. Wherever they went, they united and, above all, built churches. The clergy went together with the emigrants. We had Vladyka Seraphim here.1 He was very peaceful and set a good example to others. But towards the end of his life, the old “base” of emigres no longer here. Vladyka was disappointed and retired. So gradually we lost many clergy.

—Does the community today consist of Russians, or are there representatives of other nationalities too, including locals?

—In Venezuela newcomers are a different world. There are many Belarusians who are sincere believers, but they do not even know how to approach a priest or receive his blessing. You have to explain everything from scratch, but I am happy to do it—that’s my duty. I am glad when children come and receive Communion. This is spiritual joy for a priest.

After the pandemic we organized Christmas parties three years in a row, made pancakes on Maslenitsa (the Cheese-Fare Week), and we arrange some leisure activities and games for children. We’re doing what we can. Some Russians come, but I feel they are still far from spiritual life. They come on the day of the death of a loved one and ask me to serve a Pannikhida, for example. But I see that they know very little about church matters. I can’t demand much of them, because most of them are adults. It shocks me that I have to baptize adults: I bought a full-immersion pool for baptisms. One day a lady came to receive Communion, and when I asked her if she was baptized, she replied that she did not know! What should the rector do in this case? He should baptize her.

The Church of the Dormition of the Mother of God in Caracas. Photo: Historiasquelaten.com

The Church of the Dormition of the Mother of God in Caracas. Photo: Historiasquelaten.com

—Can you recall the most striking story of a local converting to Orthodoxy? Or just an interesting story.

—One day I was called and asked to go to Puerto la Cruz. There was a sick Greek there and I was asked to give him Communion. It seemed strange to me, because there was a Greek priest in Venezuela. I went there, heard the Greek’s confession and gave him Communion at the hospital. He was very poorly and died soon after. Then I was asked to come and perform the funeral service for him. I went again. It coincided with the Catholic Christmas, December 25th, and there were problems with traffic. But I arrived there and explained to his family that they should pray on the third, the ninth and the fortieth days for his repose. Interestingly, the Greek’s wife was a local who had converted to Orthodoxy. Their grandchildren were baptized by Catholics. But their father asked me to receive them into Orthodoxy. So I received his two daughters into our Church.

On one of my next journeys my car broke down and I had to take a bus. I was sitting next to a lady there and we started talking. We also spoke about religion. She was in her twenties and unbaptized. I asked her, “What’s your name?” She replied, “Michelle.” And it turned out that her father was a fan of the Beatles and loved their song “Michelle”! “How odd it is!” I thought. The next time I went to the Greek I baptized both Michelle and her daughter.

—Tell us about the most striking events in the life of the parish in recent years (or in its history in general).

—There was an episode that brought me spiritual joy. I heard the confessions of, gave Communion and Unction to and performed the funeral of the wife and brother of a priest in Venezuela, Fr. Paul. He also had a relative named Catherine whom I had never seen in church. She once said to me: “Kirill, I have never confessed.” I explained everything to her. She confessed very thoroughly. I gave her Communion and Unction, and she died the next day. We buried her. Two or three months later a friend of mine passed away (he was like a brother to me). He appeared to me in a dream and started dragging me somewhere, “Kirill, let’s go there!” I told him, “Wait, where are you dragging me?” He was dragging me upwards. Suddenly we found ourselves somewhere where there was white light and white curtains… And I saw the same Catherine there! My friend disappeared and Catherine appeared young to me. Looking at her, I was stunned by her fluffy red hair and her beauty! In real life I had met her when she was in her sixties and I had never seen her red hair. I exclaimed, “How beautiful you are, Granny Katya [a diminutive form of the name Catherine.—Trans.]!” She laughed. I asked her husband, “Was Granny Katya’s hair red?” He looked at me in horror, because I had never seen her photo. So he wondered how I knew it, and I replied, “I saw her.” Such moments have been imprinted on my mind and they only confirm my faith in God.

—Do you manage (if it is needed) to interact with representatives of heterodox denominations and other faiths?

—We mainly communicate with Catholics. An acquaintance of mine knew a cardinal with whom he went to school. I told him that I did not allow people to have Communion without confession. Most Catholics were no longer giving confession before Communion by then. We argued. In the end he told me, “Yes, father, we must revive this tradition—I agree with you.” But it is one thing is to say it, and another to do it.

We had very good relations with the Serbs. Unfortunately, however, there is a lot of modernism amongst them. Ecumenism destroys everything.

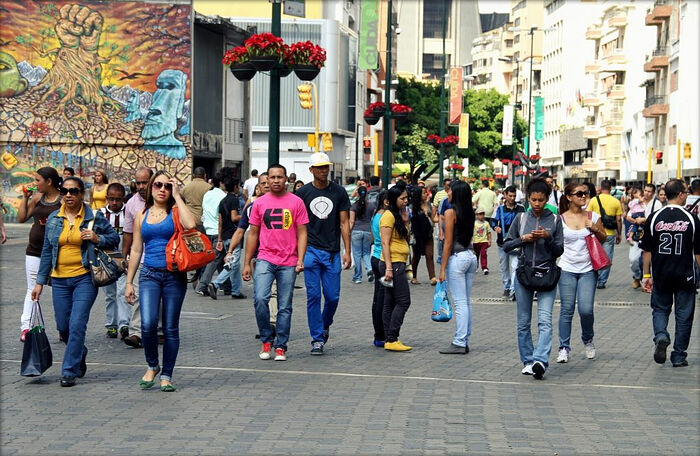

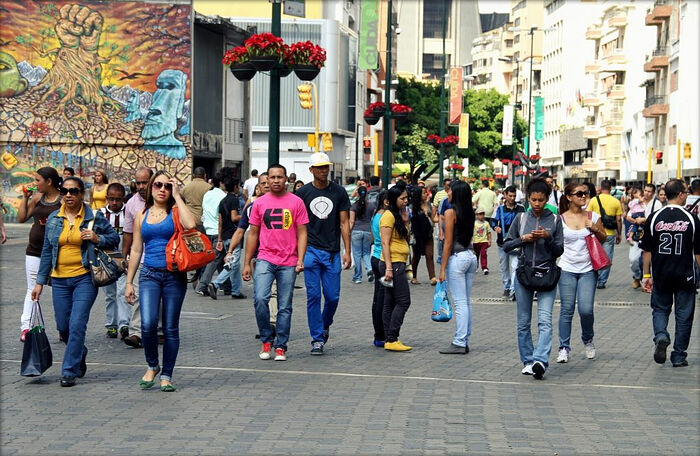

Passers-by on a Caracas street. dk1974.tourister.ru

Passers-by on a Caracas street. dk1974.tourister.ru

—What serious spiritual questions from parishioners do you as a pastor come across in your ministry?

—It depends—from the simplest and easiest to the most complex. The latest example: A mother lost her son. So some Catholics ask me for help. It is hard to explain to them that there is no Purgatory. Our Church teaches that we must pray and do good deeds in memory of the departed, but the Catholics don’t have that. Local Protestants believe in various modern propaganda, that Christ was in India or in China.

I had a difficult case, as well: A man was struggling with drugs and alcohol. My future assistant, for whom I had great expectations, was ruined by alcoholism and committed suicide. There was a young man who was drawn to the Church. My grandfather hoped he would become a priest. But God took that man—he was with his friends at sea, and drowned.

—What is the main lesson you have learned over the years of your ministry?

—Patience. More patience. Many things have to be “swallowed”. Never lose heart. I can also say that at every moment I repeat the Prayer of St. Ephraim the Syrian, which is read throughout Lent. It means a lot to me, and lifts my spirits.

I am not fearful when there are few parishioners. In my grandfather’s time I saw the church packed. And by the end of his life, he often served with only me and maybe an old lady as his parishioners. My grandfather served, and I helped him, sang and read. Modern clergy sometimes get disappointed in such situations. But it doesn’t bother me. I saw it in childhood.

—If a pilgrim (or a traveler) from Russia comes to Venezuela, which places would you recommend him to visit?

—The nature of Venezuela is a paradise. There are lovely beaches; there is jungle, which is also nice; there are mountains and snow; there is a desert; it is summer all year around; and nature changes depending on your location. I remember my brother lived in the Andes for the last few years. According to my brother, it was warm there. But when I was there, I slept under two blankets at night.

The Venezuelan Andes. lacgeo.com

The Venezuelan Andes. lacgeo.com

There are waterfalls and rivers to all tastes here. There are even crocodiles, and snakes, both venomous and harmless. There are snakes that can eat a whole boar. Piranhas live in these parts. A school of them can attack a man and eat him in just a few minutes.

There is Teleferico in Caracas, a cable car system for viewing the city. The “gondola lift” rises up to a platform, where you can relax, have a snack, take a walk, and see beautiful views of the city and nature. On the way to the top you can admire the whole of Caracas.

—In conclusion, here is our traditional question: What words from the Holy Scriptures especially inspire and support you in difficult moments of your life?

—The words about the rich man and Lazarus. The rich man didn’t care about his soul: he had lavish feasts every day; and there was Lazarus who lay beside the fence, eating crumbs from the rich man’s table, with dogs licking his sores. Both of them died. The rich man found himself in hell, and Lazarus ended up in Paradise with Abraham and Isaac. The rich man had known about Lazarus’ suffering, but he had totally ignored it. Now he was asking Lazarus for help, but there was an abyss between them. This story clearly shows us that we end up either there or here after death. Wealth is nothing—it’s temporary. Satan showed Christ that all the riches of the world were his, but they are simply dust. The Bible clearly tells us that there are two paths you can walk: either “up”, or “down”.